Marc Demarest, Director of the International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals (IAPSOP)

Last year, at a workshop sponsored by the Popular Occulture in Britain project, I gave a short talk on the ways in which some of the Twilight Mages – an extended network of commercially-minded occultists operating in the US and the UK at the end of the nineteenth century – used modern direct-mail marketing techniques and astute social engineering to sell occult lessons and device, by mail, to hundreds of thousands of people across the globe making the mages themselves in many cases fabulously wealthy in the process.

At the end of that talk, I scattered a few seeds, inviting the audience to look into a couple of the Twilight Mages whose life and work I adore, but who didn’t make it into the material of my talk. Who, after all, wouldn’t be interested in digging into the (honestly, fascinating) life and work of Professor X. O. Zazra, or O Hashnu Hara?

Digital resources like the International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals (IAPSOP) archive are seed generators, and seed germinators. For perhaps the first time, it’s possible for an ordinarily-resourced historian of the occult to reconstruct, month by month and sometimes day by day, the trajectory of a person, an institution, a practice or an idea, against the background of the larger movement. For those of us who have done so, that power – a power of recovery, and of clarity – is intensely gratifying. Big data, as it were, allows for specific, precise microhistory. That kind of ground truth feels, in this precarious time, wonderfully solid, and makes for a potent antidote to untethered theorizing.

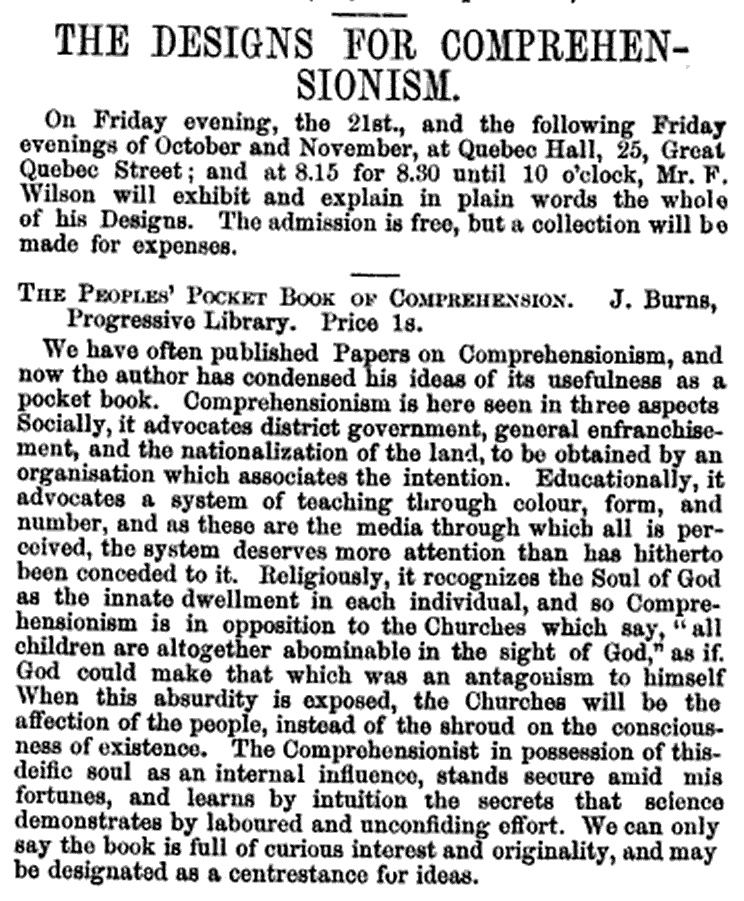

But our unprecedented collective access to the materiel of Spiritualism, increasingly in digital form, reveals much – much too much – that the synoptic histories of the movement on which we have all been raised and trained chose either to elide, or ignore. One stumbles, for example, upon the truly marvelous Captain Frederick J. Wilson, the father of Comprehensionism (surely, the most incomprehensible system of thought I’ve ever encountered) demonstrating his Science via multi-colored wall charts at the margins of a Spiritualist soiree in Dalston in 1876, sees before one wholly unploughed fields, and… passes them by, with a sigh and a wave of the hand.

I am not sure what the opposite of belatedness is, but I feel it, regularly. There is much – much too much – unsurveyed, unploughed, untended land in occult studies. Much too much yet to be done.

Some years ago, I began keeping a record of alluring paths-not-taken, in a delusive effort to convince myself that — honestly, some day, promise — I would get back to Frederick J. Wilson, or to the London instrument makers who crafted scrying crystals for Victorian matrons, or to Frederick Tennyson’s passion for astro-Masonry. Delusive, for certain – each year, the list grows longer, and the paths I have chosen to walk similarly recede, into the distance. Much too much yet to be done.

For the possible benefit of others who are looking for a path-not-taken in the study of Anglo-American Spiritualism, in order to walk ahead, or walk alone, here are a few general topics, in no particular order, synthesized from my long, delusive list. Unsurprisingly, most of these topical areas are closely related to the rich, diverse cross-border traffic at the open boundaries between the occult (in the broadest sense of that term) and popular culture, throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

1. The problem of the first decade: in both the United States and the United Kingdom, the first decade of the movement’s history (1848-1858 in the US, and 1852-1860 in the UK) are, as yet, poorly documented and poorly understood. We do not, for example, understand the role that prior occult art – particularly folkways and folk practices – played in the development of Spiritualism in the United States, or the ways in which the core practices of the movement (the rapping séance, and early automatism) spread in the US. Nor do we understand how, in the UK, upwellings of the Spiritualist impulse in three separate areas – Keighley, Nottingham and London – by three dissimilar forces (Shakerism, folk occultism and Spiritualism proper) combined with mesmeric practices like table-turning, and a trickle of appearances by American practitioners to produce, by 1860, a national phenomenon. And, importantly, we do not really understand how the secular culture perceived the initial upwellings of Spiritualism, in its midst – no one has undertaken a comprehensive reception study, in either the US or the UK, as far as I know.

2.The institutional history of the movement: we seem to have permitted the apparently self-evident notion that Spiritualism was anti-organizational and anti-institutional to become a kind of bar against the study of the (literally) thousands of ephemeral and long-lived institutions formed by Spiritualists, some of which – the British National Association of Spiritualists, for instance – were highly impactful. Little to no work has been done, as far as I can see, on the history of these institutions and the foment and ferment associated with their formation, operation and decline. Spiritualists were, as a group, great formers but indifferent operators, and their organizational triumphs and disasters remain to be chronicled and analyzed.

3. The commerce between Spiritualism and other divergent social practices, particularly vegetarianism, temperance, physical fitness, anti-vivisection-ism, anti-vaccination-ism and dress reform. Spiritualism’s passion for reform was uncontainable, and that passion expressed itself in the penetration of nearly every reform movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by motivated individuals who embraced the Spiritualist hypothesis. These divergent social practices have their histories and their historians, it is true – but few of them seem to be interested in exposing the extent to which the energy and organizational smarts of their movements depend on Spiritualism’s doctrines and fundamental optimism, and on Spiritualists, spreading the gospel of progress.

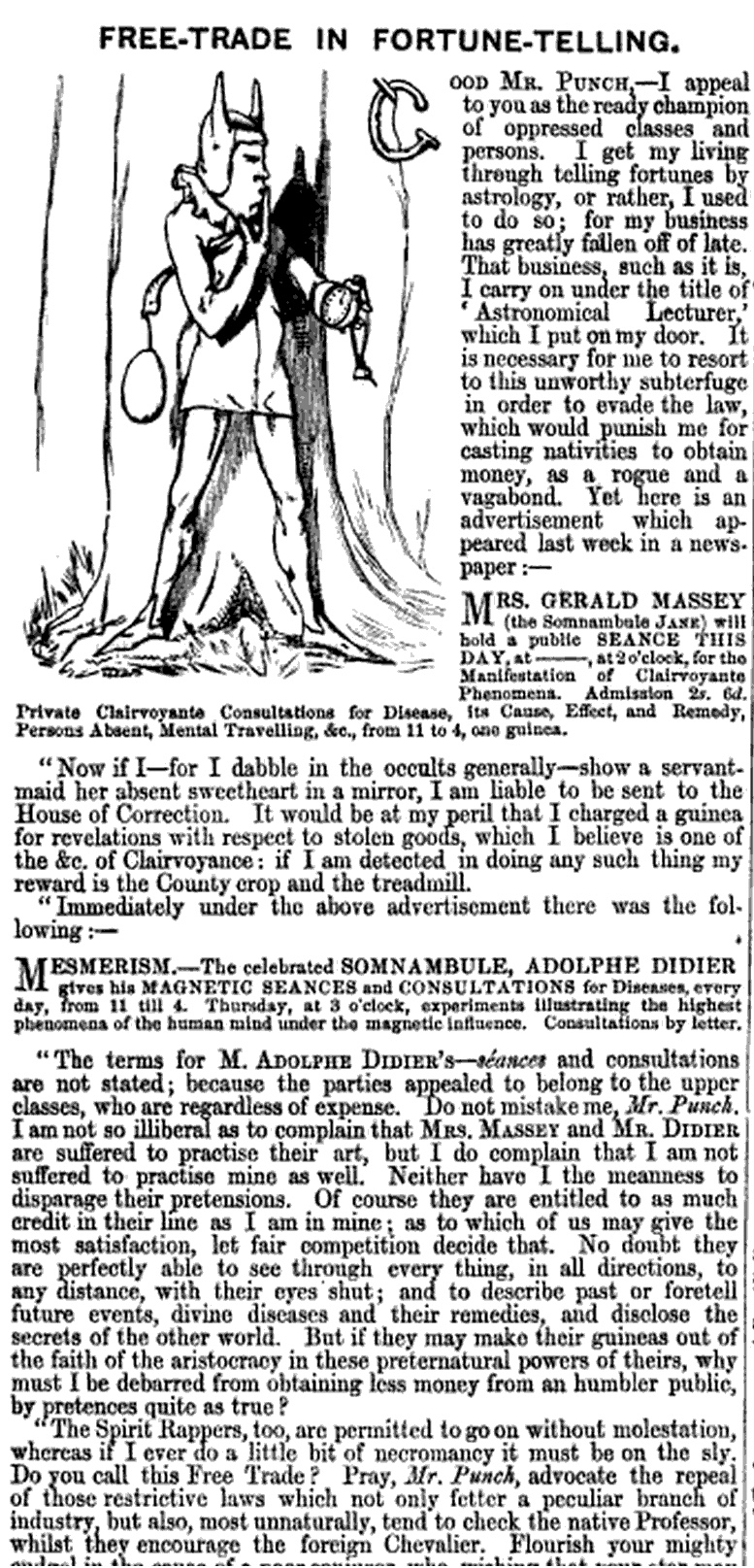

4. Spiritualism and stage magic. Spiritualism is bound up with stage magic, from its inception. Traveling magicians – and their close cousins, the traveling mesmerists and electrobiologists – prepared a massive rural audiences to receive Spiritualism as a set of phenomena; Spiritualist mediums became magicians, and magicians became (occasionally) mediums; stage magicians from the early 1850s onward made a strident kind of war on Spiritualism, and in so doing promoted it; stage magicians in the 1870s and 1880s assisted Science in (as Science thought) debunking Spiritualism. In my estimation, this field is almost entirely unploughed, by historians of stage magic and by historians of Anglo-American Spiritualism.

5. The demographics of Anglo-American Spiritualism. The recovery of so much of the periodical record of the first half-century of the movement has provided us with lists of people – literally hundreds of thousands of individuals – that ought to allow us to cease generalizing about the demographics of Spiritualism, and begin discovering – as I think we will – that the sociocultural groups from which Spiritualism drew adherents are more complex than we, today, imagine. I doubt we will ever be able to support or counter the outrageous demographic assertions of the early Spiritualists – that there were as many as 11 million committed Spiritualists in the Anglo-American world circa 1860 — but we should be able to dig into, and quantify, many interesting features of the Spiritualist demographic – including, for instance, the oft-observed fact that Spiritualism seems, in the nineteenth century, to be over-freighted with lawyers.

6. The business of Spiritualism. I spend enough of my own time in this area to be sure that the work here is decades away from being done. As a means of getting one’s living, Spiritualism was precarious, risky and in some cases highly rewarding, and the search for viable business models by Spiritualists who wished to earn as well as practice, is almost entirely untouched by historiography that has, to date, focused either on specific individuals – usually mediums – or on broad-outline synopses.

7. Spiritualism and the Law. While much time, relatively speaking, has been spent looking at the more famous court cases involving Spiritualists – Lyon v. Home, the Slade trial – little or no time has been spent investigating the broader legal contexts within which Spiritualism operated, including the laws governing inheritance, banking and currency controls, securities, lunacy, the use of the mails, immigration, identity, freedom of speech, and so forth. What work has been done in this area, has been done by legal historians, and feminist scholars, whose focused inquiries often fail to illuminate the ways in which the occult generally and Spiritualism specifically are both the adversary, and the suitor, of the Law, in the nineteenth century.

8. Spiritualism and medical practice. Spiritualism was, from its inception, a healing discipline, as mesmeric clairvoyance had been before Spiritualism’s irruption. Spiritualists sought to become physicians, to craft and sell proprietary medicines, to distribute mind-altering substances and medical devices, to found schools of medicine, to evade and to shape medical licensure laws, and in general to turn the spirits to the task of remediating the physiological and psychological effects of modernity. Medicine validated social worth, provided – notionally, at least – a more stable income than mediumship or lecturing, but also delivered, in some senses, on an old promise of the occult: the power to heal. Closely related to this, I think, is the deep interest among

Spiritualists at the end of the nineteenth century in the complexities of procreation: sexual practice, heredity, pre-natal influences, childhood education, and so forth.

9. The social network of Anglo-American Spiritualism. When Maria Hayden arrived in England in 1852 to spread Spiritualism’s practices and beliefs, she found herself immediately embraced and shepherded by an already-existing network of acquaintance, valorization and promotion, from which she (and her husband, a life-long marketeer) benefitted greatly. Less than a year later, Alfred E. Hardinge – my candidate for the title of first native English medium – was reading the works of American automatic writers, days after those works were published in New York. A novel practice – form materialization – could, and did, spread from a small community in New York to central London in a matter of weeks. How did this network operate? How is it that Anglo-American Spiritualism, from Newcastle to New Orleans to New South Wales, is from the 1860s onward so remarkably uniform, and so effectively transmissive of news and novel practices?

10. Spiritualism and literature. Novels, poems, plays – Spiritualism borrowed from mainstream culture (venerating Burns, Felicia Hemans and the Spasmodics, while providing harbors for the likes of AE and Yeats) and itself aspired to high art, no less than any other divergent social discourse of the early modern era. As often as not, when a medium was controlled by the Famous Dead, that control was: a litterateur. Some enterprising scholars are working in this rich vein already, but folks inclined to literary studies will find there is much basic work to be done surveying and mapping the literature (proper) of Spiritualism and its authors, as well as recovering the surprisingly rich reception history of that literature. Bibliographically-minded folks will find textual curiosities aplenty, shelves’ worth of uncollected stories and novels, and variant editions of texts that wait, uncollated and unannotated, for good editors.

Beyond topic areas like those on this list, there remains several hundred lifetimes’ worth of what I think of as donkey-work: the (for me, intensely pleasurable) business of building the basic factual foundations of the discipline on which others will erect their superstructures. We are not, as so many other disciplines are, blessed with well-researched, accurate and largely-complete timelines, biographical dictionaries and gazetteers, covering off the lives and doings of the thousands of characters who move on and off the many stages of the moveable Lollapalooza that was Anglo-American Spiritualism between 1850 and 1920. We don’t have standard survey course syllabi, or the texts to deliver such courses. It’s unlikely, come to that, that a dozen of us could agree on what such syllabi should contain. And we don’t, as yet, have an agreed-upon canon of primary texts.

How exciting.

There is room in the Fields of the Spirits for many, many amateurs and professionals to develop competencies, experience the thrills of discovery and insight, and collaborate with like-minded peers.

At a time in the life of the world when (often outlandish) systems of belief are everywhere ascendant, I observe: my, how green these fields are.

All images taken from the IAPSOP archives.