Michelle Foot

James Lee Byars, The Diamond Floor, 1995. (Photograph of 2017 installation).

The recent exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Dublin, entitled As Above, So Below: Portals, Visions, Spirits & Mystics explored evolving and changing ideas of spirituality through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The exhibition promoted contemplation on the wider engagement with the outside world and how spirituality endures in our everyday lives.

The exhibition was organised into four sections: Portals, Below, Above and Beyond. ‘Portals’ explored concepts of connecting with other worlds and the gateways to those realms. ‘Below’ focused on the occult, where the influence of Aleister Crowley seemed to linger omnipresent throughout. ‘Above’ displayed works of artists who express ideas of transcendence. Finally, ‘Beyond’ showed works which challenge the ideas of spirituality and what lies beyond death.

Recently there have been a number of exhibitions that focus on themes of spirituality and mysticism. These include the exhibitions on artist-mediums Hilma af Klint at the Serpentine Gallery and Georgiana Houghton at the Courtauld Gallery both in London in 2016; Beyond the Stars – The Mystical Landscape from Monet to Kandinsky at the Musée d’Orsay, Occulture: The Dark Arts at City Gallery Wellington and Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892 – 1897 at the Guggenheim in 2017; and the earlier Encyclopaedia of Everything at the Venice Biennale in 2013. Today the renewed interest in the spiritual and mystical seems to parallel the nineteenth and twentieth-century interests in Spiritualism, mysticism, and the occult in an age of anxiety and uncertainty.

Hilma af Klint, Altarpiece No 1 Group X Series, 1915. Hilma af Klint Foundation, Sweden. (Photograph of 2017 installation)

The exhibition catalogue tells us that the departure point for As Above, So Below is 1907 and the earliest works in the exhibition focused on Hilma af Klint, Annie Beasant, František Kupka and Wassily Kandinsky. Yet the works by these individuals were informed by the momentum of spiritual and theosophical ideas emerging from the nineteenth century.

The nineteenth century was a period of great change and rapid new developments in almost every sphere of life, from advances in medicine, technology and science to population growth and migration. This caused much uncertainty during the period as traditions and norms were challenged in ever-shifting situations. God died in the nineteenth century, at least according to Nietzsche. Consider, for example, the theories of evolution presented by naturalists and biologists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Evolutionary theories undermined an old worldview and challenged orthodox religious beliefs. The Origins of Species caused much of its readership to become anxious about their biological identities and uncertain about their faith. How could these new scientific ideas be reconciled with Christian beliefs? Modern Spiritualism claimed to have the answer: the central belief that the human spirit survives death and continues to live an afterlife maintained a traditional tenet of conventional religion, but the claim that these spirits were accessible to mortals in séances was an exciting new prospect. The spirits which allegedly returned through the Veil (the threshold between life and death) told mediums that they continued their spiritual evolution in the spirit world, appropriating Alfred Russel Wallace’s evolutionary theories in particular. Spiritualists invited scientists to attend their séances in the hope that the investigators would verify the spirit phenomena and confirm that Spiritualist beliefs were a matter of scientifically proven fact. This was the reason why the Spiritualist movement took ‘Modern’ as its prefix, to show it was relevant for a changed modern world, combining spiritual beliefs with new science, and addressing the uncertainty and anxiety of the age.

Fin de siècle anxiety increased as the nineteenth century approached its end. Entering a new period has often caused a fear of the unknown. Mystics and prophets have always foretold bad things will happen in the next century. As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, imperial expansion and political tensions grew in a world already subject to attacks from radicals and extremists in a manner that would appear similar to present-day terrorism. On 12 February 1894, an orchestral performance at the Café Terminus at the Gare Saint-Lazare was bombed by a French anarchist. More recently, on 13 November 2015, daesh attacked a concert at the Bataclan Theatre and on 22 May 2017 a suicide bomber targeted the Manchester Arena. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was perceived by many to be a terrorist attack against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had far reaching consequences as it put into motion the events that led to the First World War.

Nineteenth-century anxiety at the turn of the century was not misplaced, and in a sense it was prophetic of the two world wars which followed. For some, the First World War was supposed to be a cleansing, a great battle between good and evil forces, and when the good triumphed victorious humankind would be delivered from moral and material decadence. Kandinsky believed a spiritual war was also taking place on another plane – as above, so below – and this was what he depicted in his art. During both the First and Second World Wars, fear for loved-ones’ well-being and widespread bereavement saw people turn to various forms of mysticism and the occult for comfort and in order to comprehend the violence and death toll.

Steve McQueen, Running Thunder, 2007, 16mm colour film. (Photograph of 2017 installation)

Running Thunder (2007), a video projection by Steve McQueen in the As Above, So Below exhibition, was the piece which perhaps most directly asked us to confront death or the balance between life and death. A horse lies still facing the viewer and is surrounded by grass blades and meadow flowers moving in a breeze. The horse’s chest barely seems to move, if at all, it is uncertain whether or not it breathes. A fly circles the animal before finally crawling over the horse’s open eyeball, it does not flinch. The tension created by our psychological association of motion with horse-racing and the title of the work is jarred by the contrast of such stillness in the body of the horse. It is a still life, nature morte. At 11 minutes and 41 seconds long, this piece feels timeless. It could depict an equine casualty from the Somme or it could be a horse laying in a field today, yet it conveys a sense of dread which transcends time altogether.

Current affairs always seem to move faster than the summary of past events recorded in a history book. Today the global political landscape speaks of similar shifting uncertainties: an unpredictable President of the United States, the unknown relationship regarding the UK’s future with the rest of Europe during on-going Brexit negotiations, meanwhile populism continues to be cited as the source of change behind more radical political agendas. The Tories’ deal with one of Northern Ireland’s parties flagged up warnings about the possible impact on 20 year-long peace negotiations, and a hard Brexit questions the possibility of a hard border in Ireland. Countries flexing their muscles in recent years, such as North Korea, the US and Russia, have at times reminded us of pivotal events prior to the two world wars. Meanwhile the European Union tries to gather itself together as it looks back at the weakening of the League of Nations before the Second World War with an understanding of the consequences. As thousands of Syrians and Iraqis flee worn-torn territories an on-going refugee crisis continues to frustrate far-right groups who promote nationalism under perceived threats of losing a native national identity during mass immigrations. The record heat wave in June prompted headlines that cited climate change as the cause, and while we continue to battle our addiction to fossil fuels the American government pulled out of the Paris Climate Agreement. Those sensitive to environmental issues wonder how long the planet has left. The world is full of noisy and busy change, while a quiet unknown is ever-present on the horizon.

Buce Nauman, Natural Light, Blue Light Room, 1971. (Photograph of 2017 installation)

The twists and turns in the events of the political landscape can be disorientating and add to our sense of uncertainty about the future. This is perhaps best reflected by Bruce Nauman’s architectural installation Natural Light, Blue Light Room (1971) in the Below chapter of the IMMA exhibition. It is an intentionally confusing space, mixing both natural daylight and a blue artificial neon glow. The stimulation caused by two different light sources impacts the psychological state of the viewer. Nauman said of this environment, “The idea was that it would be hard to know what to focus on and even if you did, it would be hard to focus.” The shifting light outside is in a constant state of change but the consistent, unchanging blue light may be taken as a metaphor for the constant spiritual undercurrent amid turbulent secular events. Previously in 1967, Nauman suggested, “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths”.

The world is constantly changing and the exhibition in Dublin asked visitors to contemplate the spiritual responses to these changes, to view and meditate on the art, to make sense of our now so-called ‘post-truth’ world.

Mysticism, the spiritual and the occult have the power to represent the Other. Sometimes it is about escapism, searching for something other than what has become our everyday norm; sometimes it is about seeking change, looking for an alternative path; sometimes it is about finding comfort.

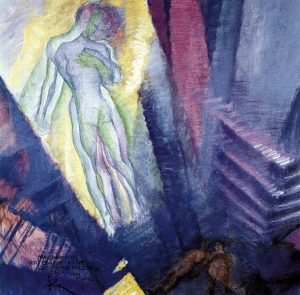

František Kupka, Le Rêve (The Dream), 1909. Kunstmuseum Bochum, Germany.

Kupka’s oil painting, Le Rēve or The Dream (1909), included in the exhibition, shows two figures laying down among tonal shadows at the bottom right corner of the canvas. Their dream or astral projection sees their disembodied spirits surrounded by a yellow aura, levitating in a colourful embrace far above their sleeping bodies. It is an image of a momentary escape from the material world to engage with the spiritual.

Being spiritual can mean many different things for different people, and the exhibition explored this. What is certain is that the artworks chosen by the curators questioned different forms of engagement and encounters with the spiritual, including the agnostic and sceptical. Art has the ability to hold a mirror up to us and helps to create a narrative which makes sense of the chaos we often find in the world around us. It can give us a focus to block out the sounds of riots, explosions and shouting politicians. Art can slow us down and channel our minds on reflection and contemplation. The exhibition asked the question about what spirituality means for us today. The curators drew upon Susan Sontag’s quote: “Every era has to reinvent the project of ‘spirituality’ for itself.”

David Beattie, The Impossibility of an Island, 2016. (Photograph of 2017 installation)

Amongst all the loud anxiety and uncertainty of the twenty-first century, perhaps the most interesting but understated installation in the exhibition was David Beattie’s The Impossibility Of An Island (2016), placed on the threshold between the Above and Beyond sections. A cymbal hangs from a thin wire and slowly moves to occasionally touch an adjacent stone, sending soft ripples of reverberation on the sound waves. This is a quiet and almost still artwork. At first the background noise of other installations drowned out the sound of the cymbal and irritated the viewer’s appreciation of this piece, but perhaps this was an intentional curatorial decision. Around the corner the drums, trumpets and xylophones of the Propeller Group’s documentary film of funeral rituals in Vietnam blasted across the gallery space, the sound of chanting came from another installation in the opposite direction. Yet quietly, rhythmically and faint, the cymbal chimed as it occasionally touched the stone, as though a spiritual otherworld attempted to make contact and the visitor need only heed and hear it. The vivid contrast between these sounds asked a simple question: how do we appreciate the spiritual during our busy, turbulent lives?

As Above, So Below: an engaging exhibition which ran from 13 April to 27 August 2017, asked the visitor to appreciate the spiritual, to reflect on the artworks and contemplate the state of an uncertain world.

Dr Michelle Foot is an art historian with research interests in Modern Spiritualism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.